He was supposed to speak in one of the literary centres in Iran, in a night of celebration of his work. He reached Iran but both events were cancelled for reasons like the venues “not being ready” and “avoiding congestion in the book fair”. The only program he could attend was a press conference on the other side of the city far from the book fair venue in Niavaran Cultural Historical Palace stopping his readers from seeing or speaking to him.

The reason was understood to be linked to the hardliners’ comments on him being a supporter of Salman Rushdie. Rushdie was condemned to death by Iran’s supreme leader Ayatollah Khomeini in 1989 following the publication of The Satanic Verses. Many muslims found the book offensive to the prophet Mohammed and protested against it. That time Pamuk stood by Rushdie.

During the press conference, Pamuk talked about his work, the impact receiving the Nobel prize had on his professional life and praised Iran’s culture and its people. However, there was one serious issue that he briefly mentioned and passed. Pamuk’s books have been published by at least eight publishers in Iran, many of them don’t have any permission to do so!

His books are censored without his knowledge, and published and sold outside of his control. He expressed his mixed feelings about this problem; he wants to be read in Iran and he is happy that his books are translated in Persian but he wants them to get to his Iranian readers based on the international conventions on copyright and by a single publisher and translator.

Iran is not a party to the Berne convention for the protection of literary and artistic works and Pamuk is not the only writer to be denied of his rights. One of the reasons that Iran won’t join any international intellectual property treaty is censorship. No publisher can guarantee to publish a book intact. This applies to other creative products as well.

But what exactly happens to a book after censorship? Do we have a clear idea how for instance Orhan Pamuk’s works are presented to his fans in Iran? You can find lists of ‘forbidden’ words or notions that have been removed from books in the process. Of course there is no official guideline for it and ‘red lines’ tend to change from one government to the next.

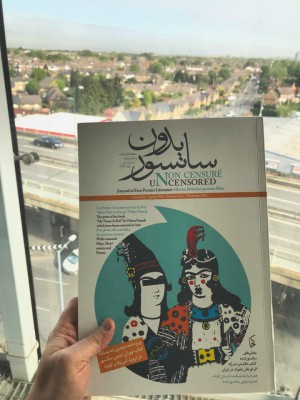

The good news is, recently, a group of authors outside Iran came together and started a quarterly trilingual magazine (Farsi, English and French) to investigate the depth of the matter. Naakojaa publishing in France is sponsoring and leading this magazine which includes articles, analysis and commentaries about the history, aspects and impact of censorship on Persian literature; poems and short stories removed from books in Iran for their ‘unpublishable’ content, and even following #censorship in Farsi to monitor and report on different cases of censorship in other art forms and media.

For me personally, the most amazing section was the Portfolio. In every issue, they are going to pick a favourite or best-selling book published in Iran, compare it to the original language – or in some cases the language it was translated from- and detect all the missing pieces.

The pilot issue of the Uncensored magazine was released in the Tehran Book Fair, Uncensored in London. The first Portfolio is dedicated to the acclaimed book My Name is Red, by Orhan Pamuk. After a comprehensive comparison they found 56 cases of censorship. The pages and lines of each censor’s invasion is specified and you can follow them through the book.

This document is an exceptional testimony showing how this suppressive system works. Orhan Pamuk said that he is ‘dissatisfied’ with this situation while he was in Tehran. The fact is, the situation is outrageous and unfair to all the community.