The early years

After completing his mandatory ten-year military service at 27, Lee Ji-myung earned a degree in geology, then became chief engineer in a coal mine, a post he held for 24 years. During that time he wrote nonstop, ever aware of the life-or-death imperative of meeting the ideological expectations of the Workers’ Party of Korea (WPK). In 1985, his one-act play Loyalist earned him ‘candidate member’ status in the Chosun Writers Association, a state body that effectively industrializes the penmanship of talented North Korean writers, who churn out propaganda to order.

Unlike the ‘regular members’, who were the Association’s in-house staff writers, a candidate member’s job was to produce material when instructed, while still working another full-time job. Drama was his forte, so Lee was often required by the regional branch of the Propaganda and Agitation Department to create plays glorifying the WPK. Lee wrote about 300 such pieces over 15 years.

“I was a government-used writer.

Looking back, I am very much ashamed.”

In an email interview with the IPA, he explained: ‘They were works of short drama, stirring choral poems, witticisms and so on to “enlighten the masses” based on the Party’s principle of literature, and to propagandize by building up the “leader first” doctrine and socialism as master.’

‘I was a government-used writer making up the picture of typical loyalists, who would praise the Leader and the Party and even sacrifice their own lives for the sake of the regime, through all of those 300 works,’ he said, adding: ‘Looking back, I am very much ashamed.’

Defection and rejection

In 1991, aged 37, Lee became aware of the social, political and cultural realities of South Korea during an official visit to China when he read South Korean literature for the first time. Over the following decade his disillusionment gradually grew to bitter resentment and roused dreams of a life over the border. In the end, it was the ‘Arduous March’ — the catastrophic famine that killed hundreds of thousands of North Koreans between 1993 and 2000 — that drove him to risk everything and defect.

In 1991, aged 37, Lee became aware of the social, political and cultural realities of South Korea during an official visit to China when he read South Korean literature for the first time. Over the following decade his disillusionment gradually grew to bitter resentment and roused dreams of a life over the border. In the end, it was the ‘Arduous March’ — the catastrophic famine that killed hundreds of thousands of North Koreans between 1993 and 2000 — that drove him to risk everything and defect.

Lee tried in vain to convince his wife to escape with him, and she angrily demanded a divorce. His daughter was married and living in another part of the country, so Lee set out alone. He crossed into China over the border-forming Duman (or Tumen) River, a popular escape route despite the waterway’s high levels of pollution and deadly border patrols along its banks. After a short time living and working in China, Lee walked into a South Korean embassy and asked for exile, finally entering the Republic of Korea on 3 November 2004. His wife and daughter still live in North Korea.

Over the past 12 years, Lee Ji-myung has discovered the hard-earned fulfilment of writing as a free man. He has published numerous novels and stories, as well as works that have been adapted as radio plays and broadcast into DPRK. He is now in the closing stages of a lengthy novel called Liability.

In addition, Lee has devoted himself to helping other North Korean writers find expression, through his work leading the North Korean Writers in Exile PEN Center, which includes publishing an annual volume of literary works by fellow defectors.

Literary wasteland

Although North Korea, which he contracts to ‘NK’, boasts a near 100% literacy rate, Lee says the country has no ‘real’ literature, since everything in print echoes the Party’s worldview.

‘We cannot regard NK literature as literature,’ he says. ‘It’s a long time since the purity of literature disappeared from the NK literary world. There are only works by those who strive to conform to and consolidate the NK political system — which they as writers were ordered to create — idolizing the Leader and loyalty to the Party.’

Nothing is published without the government’s say-so, and writers must conceive and create according to stringent literary principles laid down by the WPK. Self-expression, for instance, is condemned as the treasonous act of putting self before state

“It’s a long time since the purity of literature

disappeared from the North Korean literary world.”

A sad example Lee provides of what happens to a writer who strays is Cheon Se-bong, a once-popular North Korean author whose novel A New Hill with Floating Mists failed to pass muster and led to his dramatic fall from grace. The novel is an unremarkable portrayal of a man born into poverty who becomes a revolutionary against Japanese imperialism. The protagonist falls in love with a doctor’s daughter, who falls pregnant with his child, but social pressures drive her to marry the son of a rich landowner.

Party censors found that the plot’s clash of classes and its tragic outcome violated the ideology of humbling the ‘evil’ landowners by allying them to the working class. According to official literary policy, the poor revolutionary should have won the middle-class girl’s hand in a noble triumph over his oppressors. The book was banned and its author banished to an isolated farm to serve out a sentence of 12 years’ labour, where he was required to ‘rebuild his quality as a literary soldier for the Party’.

No rights, no copyright

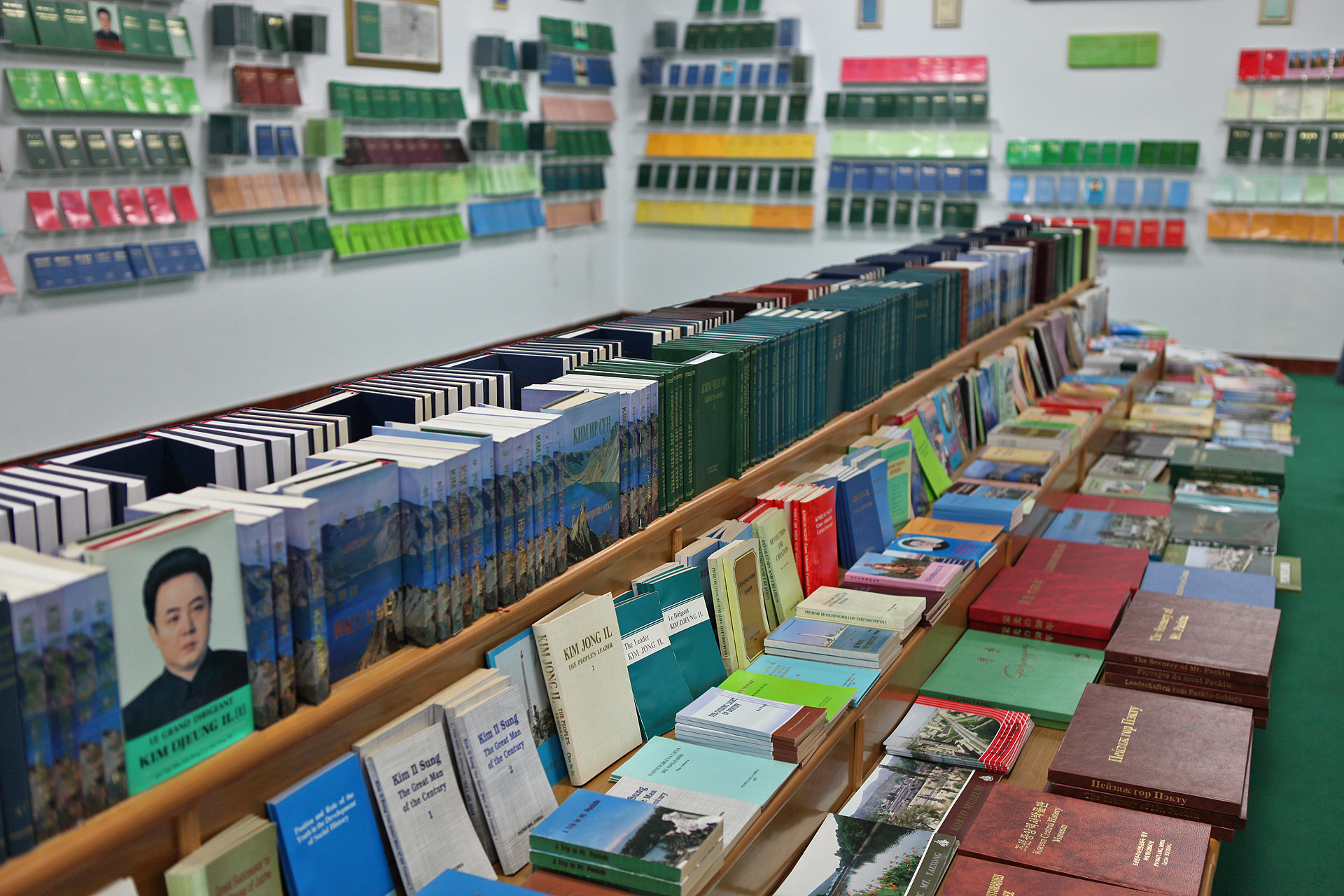

Not surprisingly, all publishing houses in the DPRK are government owned with specific thematic output, including the Workers’ Party of Korea Publishing House (ideological and cultural works by Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il); Literature & Arts Publishing House (bulletins for Chosun Writers’ Association, books and magazines on literature and the arts); and the Foreign Languages Publishing House (foreign language books and periodicals for propagandizing the North Korean project overseas).

Consequently, Lee says, ‘there is no space in NK for a private person to publish things of their own free will’, and the mere notion of earning income through copyright is anathema, despite DPRK joining the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) and signing up to the Berne Treaty in April 2003. ‘In NK it is not allowed for publishers either to have professional rights, protection, freedom of speech or commercial copyright protection, or even to access or possess information on international copyright laws. Intellectual property rights serve as a gift of honour, and the ultimate honour for NK writers is to be named a “Kim Il-sung Laureate”, which bestows on the winner additional basic provisions, such as meat, oil and cigarettes.’

Consequently, Lee says, ‘there is no space in NK for a private person to publish things of their own free will’, and the mere notion of earning income through copyright is anathema, despite DPRK joining the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) and signing up to the Berne Treaty in April 2003. ‘In NK it is not allowed for publishers either to have professional rights, protection, freedom of speech or commercial copyright protection, or even to access or possess information on international copyright laws. Intellectual property rights serve as a gift of honour, and the ultimate honour for NK writers is to be named a “Kim Il-sung Laureate”, which bestows on the winner additional basic provisions, such as meat, oil and cigarettes.’

“There is no space in North Korea for a private

person to publish things of their own free will.”

Yet, despite the paucity of literary choice and anti-association laws preventing the formation of book clubs, North Koreans love to read, Lee says, and a limited range of translated fiction has made it past the censors. These include Russian heavyweights The Mother, by Maxim Gorky; Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace, Resurrection and Anna Karenina; and Ostrovsky’s How the Steel Was Tempered. French classics the Count of Monte Cristo (Alexandre Dumas) and Les Misérables (Victor Hugo) have also been green lighted. Foreign crime novels are strictly forbidden, adjudged as they are to glamorize crime and encourage people to challenge the rule of law. Security service personnel alone have access to such works due to their presumed value as crime-busting manuals. At times, these verboten detective stories find their way onto the streets, where people read them quickly and hand them on, in defiance of the risks if caught.

Lee explains: ‘Security personnel found to be responsible for allowing these books to be distributed are dismissed and face heavy legal consequences. Of course, there are rare cases where books published in South Korea or the capitalist world are smuggled in. But if caught, this is considered a serious crime, and leads to either life in a labour camp for political prisoners, or the death penalty.’

Real-life literary hero

As with all epic tales of oppression, heroes emerge whose courage shines a light of hope. Lee says that a subversive rebel writer has emerged from the North Korean system who is managing to get his manuscripts over the border to South Korea and into print. He believes the writer is a bona fide literary Zorro who is risking his life for his art, and not a defector writing from the outside.

‘Currently, Accusation, a collection of novels written by the writer, whose pen name is ‘Bandi’, from the Chosun Writers’ Association, was smuggled from NK and published in South Korea, even reaching readers overseas. It is certain that the book was written by a NK writer, judging from the content of the work, but we don’t have any information about the author, such as his real name, job or location.’

Lee (pictured left with members of the North Korean Writers in Exile PEN Center) asserts that PEN has no links to Bandi, but that if a writer should surface who is prepared to be published overseas, then North Korean Writers in Exile PEN Center is ready to help and provide support in any way it can.

Lee (pictured left with members of the North Korean Writers in Exile PEN Center) asserts that PEN has no links to Bandi, but that if a writer should surface who is prepared to be published overseas, then North Korean Writers in Exile PEN Center is ready to help and provide support in any way it can.

That said, Lee fears helping North Korean writers from abroad is an insurmountable challenge. ‘It is literally impossible for world publishing circles to help NK writers. If you contact a national representative, they will say there is freedom to publish and freedom of speech in NK. Literature is the Party’s thought weapon, and writers are revolutionaries who must share their destiny with the Party.’

“Literature is the Party’s thought weapon, and writers are

revolutionaries who must share their destiny with the Party.”

However, he says it is possible to help DPRK writers through the North Korean Writers in Exile PEN Center, which joined the international PEN network in 2012. Its writer members are currently managing to reach their friends and loved ones in the DPRK via ‘a third country’, and the organization manages to distribute foreign publications inside DPRK. Naturally, Lee did not provide details of how this is done.