The IPA has a Freedom to Publish Committee and also a Freedom to Publish Prize, the Prix Voltaire.

As the Chair of the IPA’s Freedom to Publish Committee, Kristenn Einarsson notes “What might be surprising is that there are freedom to publish issues in almost every country. My country, Norway, ranks highly on many freedom of expression indexes, sometimes on top, yet we still have issues within educational publishing”.

The issue is worldwide and complex. So, what leads to reduced freedom to publish around the world?

For Mr Einarsson it varies “In some places, it is governments and state regimes that prevent the publication of material or works deemed to be ‘dangerous’ or ‘inappropriate’. In other cases, there are pressure groups (religious, social, commercial) trying to prevent publication of certain information. Increasingly, large technology companies are influencing, often secretly or behind our screens, what we as readers and consumers can and can’t see. The significance of this sometimes overt and at other times insidious manipulation of what we are allowed to read is simple: laws that prevent freedom to publish must be constantly challenged — there are actually very few instances, or none — where public welfare is increased or maintained by the blocking, removal or censoring of information.”

IPA President, Michiel Kolman echoed some of these comments in a recent Op-Ed in The Bookseller on self-censorship, noting that “the reason [for self-censorship] is usually fear. The source of that fear can be diverse: fear of punitive action from the state; fear of legal action from others through draconian libel laws; fear of a violent reaction of extremist religious groups; fear of public pressure.”

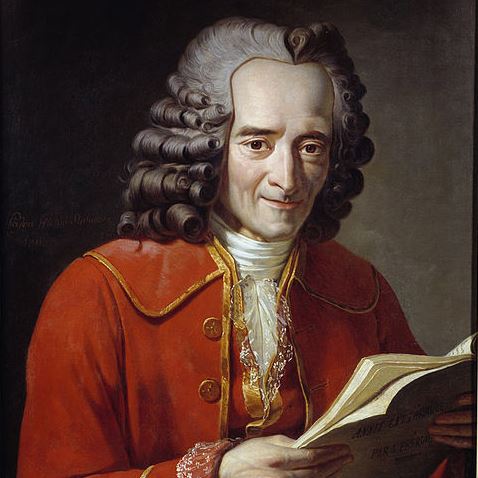

Visions of what represents freedom to publish can differ. The IPA’s Freedom to Publish prize is named after Voltaire, the French Enlightenment philosopher and writer who is often credited with saying: ‘I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.’

For Kristenn Einarsson “Freedom to publish means that publishers must be allowed to publish all that they deem worthy of publication, even and perhaps especially if those works challenge the boundaries established by the society they operate in.”

For the Publishers Association of China however, the onus is more on the reader and their right to read. “Only when the Chinese people’s desire to read is completely satisfied can we consider the freedom to publish has come to full fruition in the People’s Republic of China.”

These differing views suggest that, if anything, there is a spectrum of the freedom to publish, and that the question of whether there should be limits to the freedom to publish can also prove controversial. While some consider the freedom to publish as absolute, others cite public safety and the protection of children as areas where action to curb absolute freedom may be justified.

Given these different interpretations, it is perhaps no surprise that local action and expectations for international involvement in the freedom to publish are different. The evolution of the local market can also be a factor in where national associations choose to focus their efforts.

The Publishers Association of China considers its work in this field is best achieved through its private publishing committee: “Over 1000 private publishers have emerged across the country, which effectively put an end to decades of domination of the Chinese publishing market by state-owned publishing houses.” They note that “in 1980, only about 20,000 titles were available in the Chinese book market. In 2017 alone, new titles and reprinted ones available in the Chinese market amounted to 500,000 titles.”

As a result, the IPA’s work on this issue is not always universally welcomed and while some publishers’ associations support the attention that the Prix Voltaire brings to their own country’s political situation, others feel that it is intrusive and not where the IPA can bring the most value to the international publishing community.

For example, the 2017 Prix Voltaire for joint winners, the publisher and writer Turhan Günay and the publishing house Evrensel, was very positively received by the local publishing community in Turkey.

In contrast, the reception in China of the awarding of the 2018 Prix Voltaire to the Swedish, Hong Kong-based publisher Gui Minhai has been very different. Press coverage in China (and sometimes abroad – to much criticism over what represents balanced reporting) has focussed on Gui Minhai’s reported driving infraction and the allegedly poor quality of his publications. For the Publishing Association of China, “The IPA’s two pillars might have done their share in promoting and protecting global international publishing. However, the situation today is worlds apart from 1896, the year the IPA was established. The IPA ought to take it upon herself to look after the interests of publishers all over the world. However, this responsibility is beyond the IPA’s capacity under the present global circumstances. It would be more appropriate for the IPA to do a good job in enhancing communication and collaboration between international publishers, rather than focusing on political issues in a certain member country.”

As the IPA’s Chair of the Freedom to publish committee notes, “if we look back at previous winners of the Prix Voltaire, almost all of them had faced arrest or conviction for crimes in their home country. Equally the quality of the published works is very subjective and not something we are here to judge.”

So, what does the future hold for IPA’s work in this field?

For PAC, “Between nations there are differences in cultural traditions and social systems. Between those of us in the publishing industry there are differences in modes of management and patterns of development. Therefore, different countries have their own concerns as far as the issue of freedom to publish is concerned. It is up to the countries themselves to act on their own situations to ensure the freedom to publish on their lands.”

In contrast Kristenn Einarsson is unwavering in his desire to bring the industry together: “It is important that the publishing community, all over the world, stands together and supports the necessity of challenging all laws and actions that prevent the publication of work or information for anything other than very strict reasons of public safety — and those reasons must be constantly questioned and scrutinised. I think IPA has to do this, even if local members associations do not agree.”