Michiel Kolman (MK): DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion) has been in the news recently with Melinda French Gates announcing major donations toward “doing urgent, impactful, and innovative work to improve women’s health and well-being.” Two notable recipients were the directors of organizations supporting men and boys – the American Institute for Boys and Men and Equimundo Center for Masculinities and Social Justice.

This seems counterintuitive: surely we should invest in more female scientists, for instance, or more women at the senior and executive levels in our publishing houses. Can we explore what’s going on here?

Porter Anderson: You’re right, Michiel, even in this spring’s overheated news cycle, it really did raise some eyebrows when such a thoughtful philanthropist as Melinda French Gates made a point of funding two programs for boys and men as part of her programming for women and girls.

But her timing was great: One of the most touching comments I’ve heard on the subject came just a month later, in April, from the work of Norway’s Men’s Equality Commission. In getting ready to release their landmark Equality’s Next Step report that proposes a new framework of rights for men, the committee wrote that they’d found, “Many boys and men do not feel that equality is about them, or exists for them.”

And yet so many of us think that men and boys have no worries about equality, right? Doesn’t that sound exactly like so many women and girls have felt?

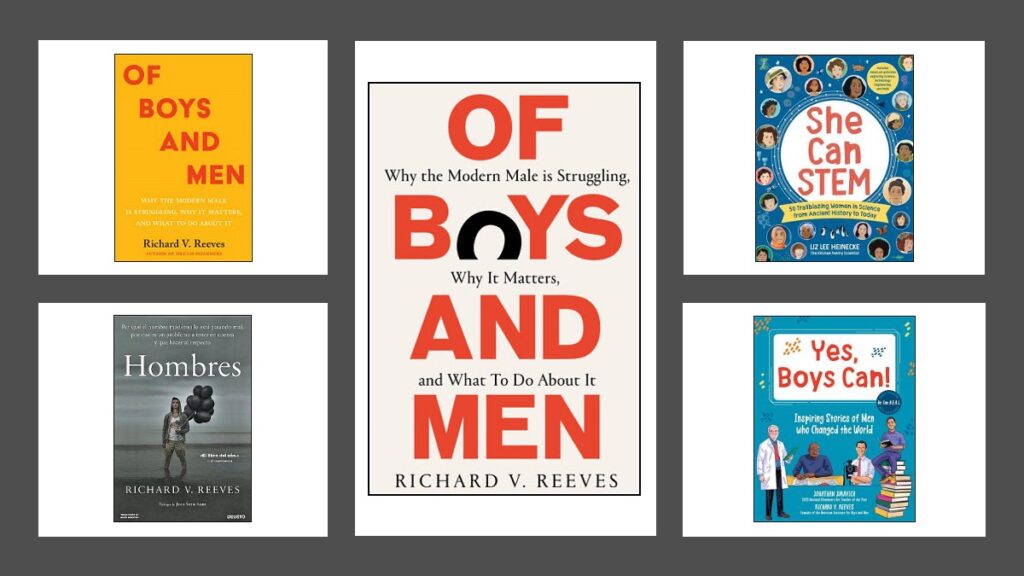

When French Gates announced her grants, she helped highlight the research of the Brookings Institution scholar Richard V. Reeves. He established the American Institute for Boys and Men after the late-2022 release of his landmark book, Of Boys and Men: Why the Modern Male Is Struggling, Why It Matters, and What to Do About It (Brookings Institution Press).

Reeves’ work in the last 21 months has pointed out, among other points, that:

- “In the average school district, boys are almost a grade level behind girls in English language and arts (there is no gap in math).”

- “The risk of suicide is four times higher for boys and men than their female peers and has risen by more than a third among younger men since 2010.”

- “Male deaths before the age of 65 resulted in over 4 million years of potential life lost in 2022, three times the number for women.”

- “At the university level, men are earning only 42 percent of the degrees conferred in higher education.”

Young men are having deepening trouble managing and hanging onto their relationships, their marriages, their families, their homes, their careers, their health, and their self-esteem. The explanation, Reeves has written, “is not that young women do not have problems. It is that boys and young men have problems, as well. Two things can be true at the same time.”

Kolman: In the publishing industry, for the countries where we have gender diversity data, we typically find that there are many more women than men working in our publishing houses — percentages like 75-percent female are pretty typical. What are the implications of the men-and-boys issue for publishers when we focus on the workforce?

Anderson: As you point out, Michiel, the book publishing workforce in many markets is made up of more women than men. This is not the case in every market; some have a better gender balance than others. And in my experience, the women in publishing are gifted, committed, highly skilled professionals. The concern is that a workforce staffed at between 70 and 80 percent women (a) sends a signal to the world that publishing and reading are not for men, and (b) this can mean that the industry isn’t seen by many talented male careerists as a business that they can or should consider.

The last 10 or 15 years have shown us what terrific work many women in publishing are doing, with a growing canon of outstanding books for girls. These focus on great women in history and on the importance of young women considering career fields once seen as being for men only.

Adding men to the workforce could mean that more content similarly beneficial to men and boys might be produced. In fact, the superb job that women have done in creating empowering, uplifting, inspiring books for young women is something that should guide and encourage men in publishing: women could be valuable publishing mentors to men, to help them craft seriously enriching literature for males, both in their boyhoods and in adult life.

Publishing executives have a chance today to think about whether they’re making a serious effort to bring men and boys into the readership. So much of the industry’s revenue is dependent on female consumers and readers. Why leave “male money” on the table? If more men joined the publishing workforce, then more timely, enticing, and ennobling content for boys and men could be produced, making the book business overall a more equitable industry and getting more content into the marketplace that could answer what parents sometimes report is a dearth of good books for their sons.

In 2017, Sophie de Closets, then the CEO of Fayard (now Flammarion) said to me about publishing in France in an interview, “When you look down [the line] you only find women. The problem will be – in a few years, in many countries – to find talented men, actually, who want to work in publishing. We have to have balanced people, in charge and not in charge, at every level in work. Only white women? That’s not healthy.”

Kolman: Publishers also contribute to DEI through what we publish. For instance, inclusive children’s books can make a real difference. Is there also a publishing content aspect to the men-and-boys issue?

Anderson: I’m glad to say there’s an example of exactly this releasing on October 22 and being presented at Frankfurt by Quarto’s Quarry Books division: Yes, Boys Can! Inspiring Stories of Men Who Changed the World, is a book co-authored by Richard Reeves and Jonathan Juravich, with illustrations by Chris King.

This is a follow-up to Quarto’s She Can STEM: 50 Trailblazing Women in Science From Ancient History to Today by Liz Lee Heinecke, which was released earlier this year (Quarry, February 13).

The idea of Yes, Boys Can! is much like the mission of She Can STEM, which helps girls consider STEM careers that many might have thought were only for guys. Yes, Boys Can! is based on the “HEAL” professions that Reeves discusses in Of Boys and Men – HEAL industries are in health, education, administration, and literacy. Those industries need men. And men need to consider careers in these disciplines, not least because younger fellows need more male role models outside the predictable walks of life.

Quarto’s Yes, Boys Can!, developed by Quarry editor Jonathan Simcosky, is a great example of a boys’ book designed to help and guide and empower young male readers, in the same way that similarly powerful books have been helping girls for years.

In addition, if publishing can cultivate new hires among men as well as women, then more content for adult male readers can be produced, as well, capturing more of the men’s market.

Reeves has a wonderful anecdote in his book about his 6-year-old son Cameron on the way back from a doctor appointment. Until that day, young Cameron had been seen only by women physicians in the English National Health Service. Cameron turned to Reeves and said, “Dad, I didn’t know that men could be doctors.”

And there’s the bottom line. If half the population feels that publishing is a “women’s industry” and doesn’t join the book business’ workforce to help create more content for men, then the business is falling short of the DEI goal of reflecting the societies it serves. What’s needed is hiring equity for men and women, both for the good of the industry and for the cultures it serves.

Kolman: What do you say about the criticism that investing in men and boys — who are typically born with more privilege than women and girls — will be at the expense of supporting female equality?

Anderson: Melinda French Gates gave a great answer to that question when she said that better boys and men are better for girls and women. And many of us are lucky enough to know some men whose own stable, healthy selfhood seems to help them be better colleagues, friends, partners, and spouses to the women in their lives. They’re superb examples for the rest of us.

What’s more, there are reasons that Reeves’ research-based book has been so successful. (When released in the UK by Swift Press by Diana Broccardo and Mark Richards, it sold more than 20,000 copies in its first year and it has been translated into at least 10 languages.) One of the things Reeves is applauding in this spring’s Norwegian report for men — is, as he puts it, that it “breaks out of zero-sum thinking, insisting correctly that greater attention to boys’ and men’s challenges will strengthen equality policy, not weaken it.”

This is such an important point. It’s critical to the discussion.

The perfectly understandable reason that it can be hard to talk about what boys and men need is that women can so easily feel that they could lose the progress they’ve made in the last 10 to 15 years. And that’s not nearly enough progress. Much more must be done to bring women and men into equity in so many parts of life, let alone in chances at executive-level seats, which women still struggle unfairly to achieve in publishing.

Reeves has been a champion for saying this with empathy and compassion and practical intelligence. He writes, with the urgency of the moment, “Helping boys and men is the right thing to do in itself. But it is also the right thing to do for women and girls. In the long run, a world of floundering men is not likely to be a world of flourishing women. Broadening the gender equality movement to include men will not hinder the progress of women. Failing to, just might.”

Kolman: Where do you see this men-and-boys movement going? Are there any long-term implications for the world of publishing?

Anderson: I hope there are. The deterioration of the collective self-image of young men that Reeves’ research is documenting — the depression among so many youths who have been told that their masculinity is “toxic,” the stereotype of the unmarried 35-year-old living in his parents’ basement and playing video games all day and night — these things are real. In fact, a leading masculinities expert, Michael Kimmel predicted this debilitating extended boyhood in Guyland: The Perilous World Where Boys Become Men (HarperCollins, 2008), to this day a compelling read.

When it comes to male self-esteem problems, the echoes of women’s struggles are startling. Have a quiet talk with the parent of a son. Ask how he’s doing. Soon you’ll hear these issues coming up, worries, anxieties.

So it’s a humanitarian challenge — like the one that publishers have valiantly and expertly helped young women with. As Reeves points out, today we see so much marvelous progress for girls and women. I recommend that women as well as men read Of Boys and Men. We know how much the world of literature and publishing can do for any sector of society, because we’ve seen it done for women and girls. And it’s great to see so many women excel now, in their educational accomplishments, their self-esteem, and their careers.

In the book business, we have an extraordinary example of career encouragement for women in the PublisHer network that IPA’s past president Bodour Al Qasimi established and has led so faithfully. Information, mentoring, collegial support can all go a long way to help making book publishing a welcoming place for men, just as these things do for women. And that can mean serving the marketplace with a reading sphere that supports everyone.

The struggles that boys and men are encountering are not the conscious fault of anyone — certainly not of the many fine women in publishing! But boys and men need the help of the book industry, just as women and girls have needed it. And it’s generous of you, Michiel, and of IPA, to open this exchange about a problem that’s more pervasive and damaging than many people realize it is.

The last time I spoke with the Yes, Boys Can! editor Jonathan Simcosky at Quarto, he said, “Maybe paying some attention to boys is the next frontier for gender equity.”

He may be right. And publishing can help.